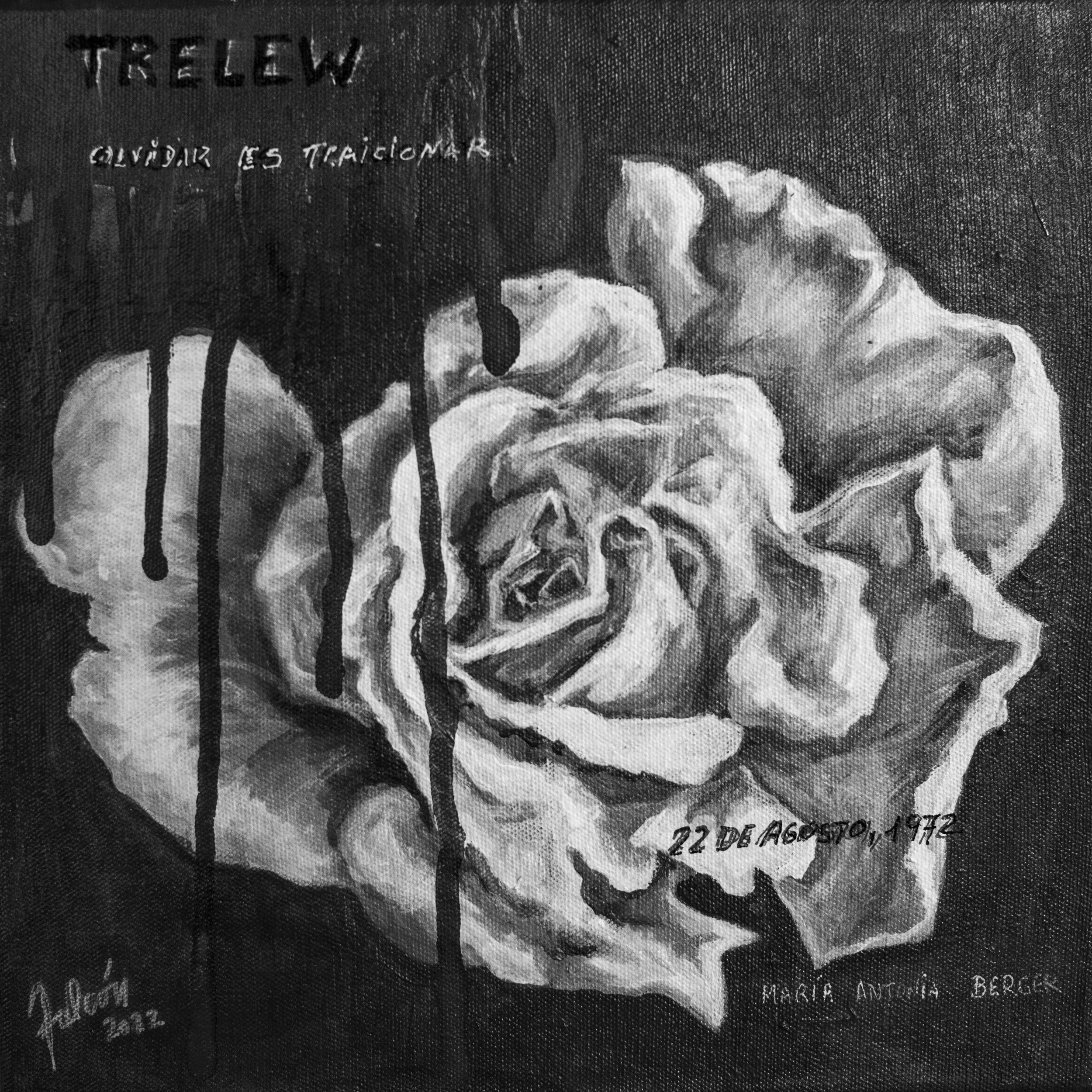

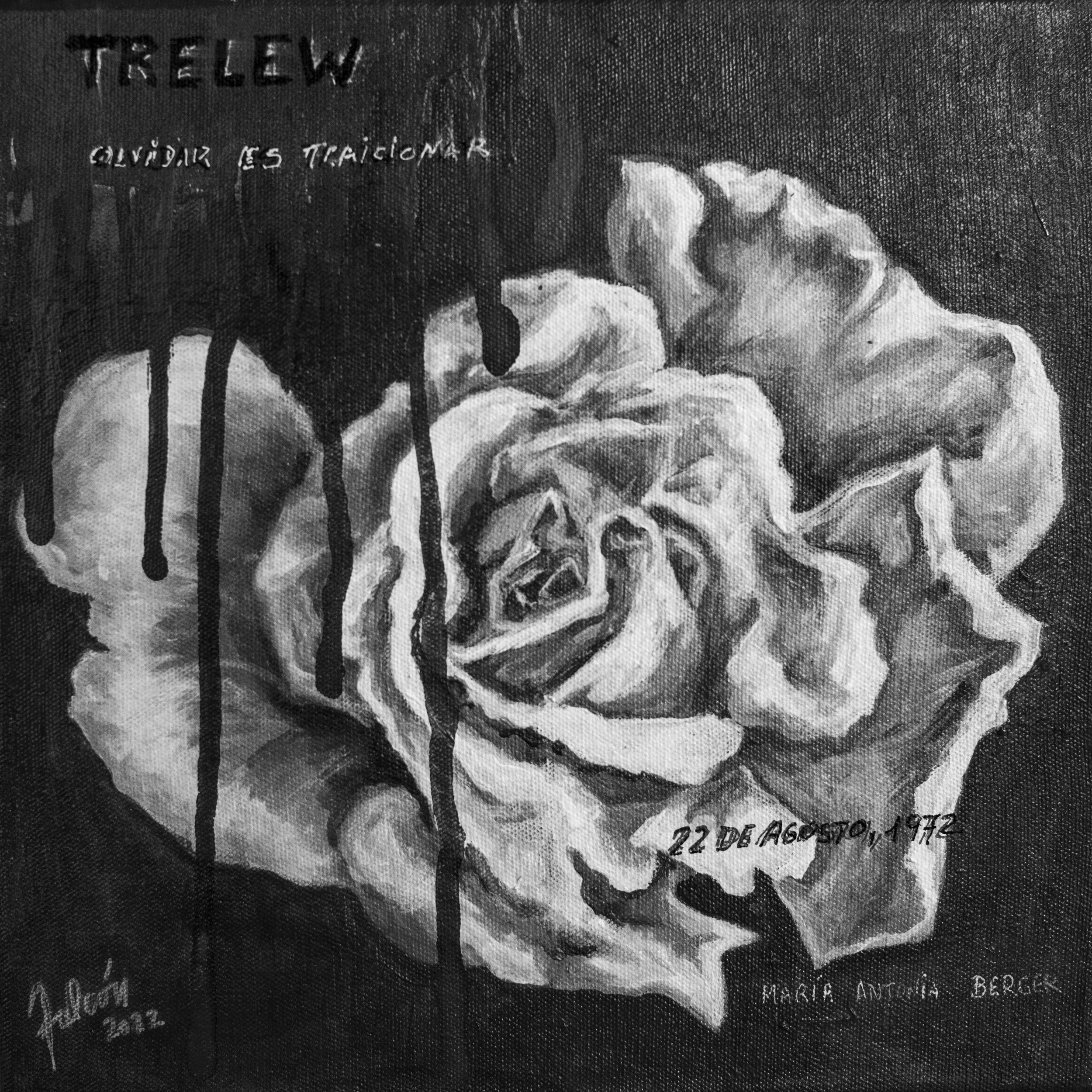

A central theme of the 50th anniversary commemoration of the Trelew Massacre was the importance of remembering—remembering relatives who opposed state terrorism and were themselves cut down by state violence; and more broadly, remembering a time when countless others were imprisoned, tortured, disappeared and killed at the hands of the military. As Elba Facon, a student from Buenos Aires, titled her painting of a white rose on display in the Centro Cultural por la Memoria [Cultural Center for Memory] in Trelew (one of many artistic expressions of the sentiment), Olvidar Es Traicionar—“To Forget Is to Betray.”

The prison cells that remain at the naval base where the Trelew Massacre occurred reflect the dimly-lit and claustrophobic conditions under which the 19 fusilados [the ones who were shot] were held in their final days. And yet, as their families toured the facility during the 50th anniversary commemoration, one could imagine the prisoners’ commitment to resistance and to one another that also occupied that space.

The Massacre took place in a confined corridor flanked by the prison cells which the 19 fusilados were ordered to vacate on the night of August 22, 1972, moments before they were shot. When visitors were allowed into the Naval Base during the commemoration of the Massacre, they had to pass through such a corridor, a space whose narrowness seemed to evoke the oppressive spirit of what had transpired there.

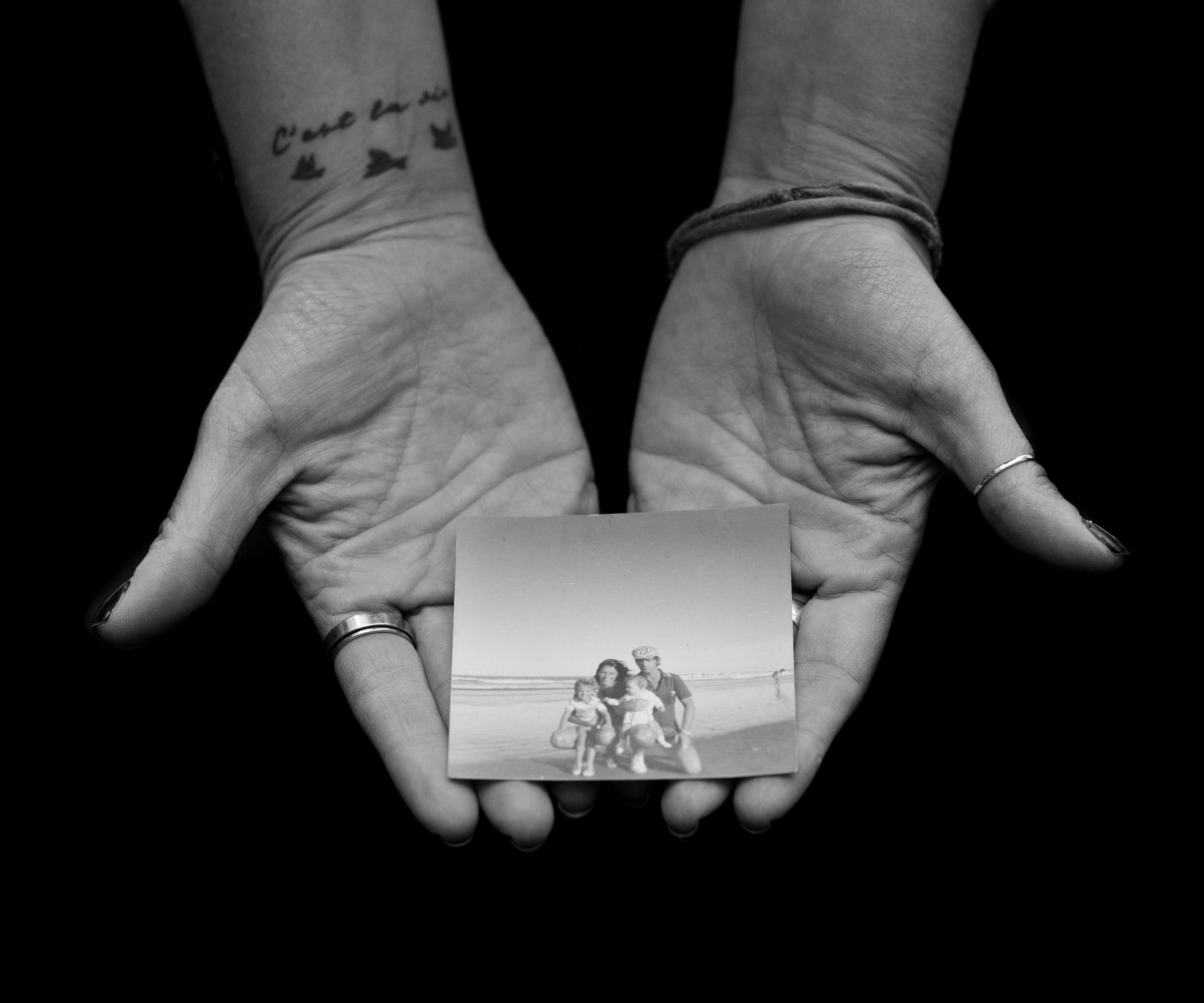

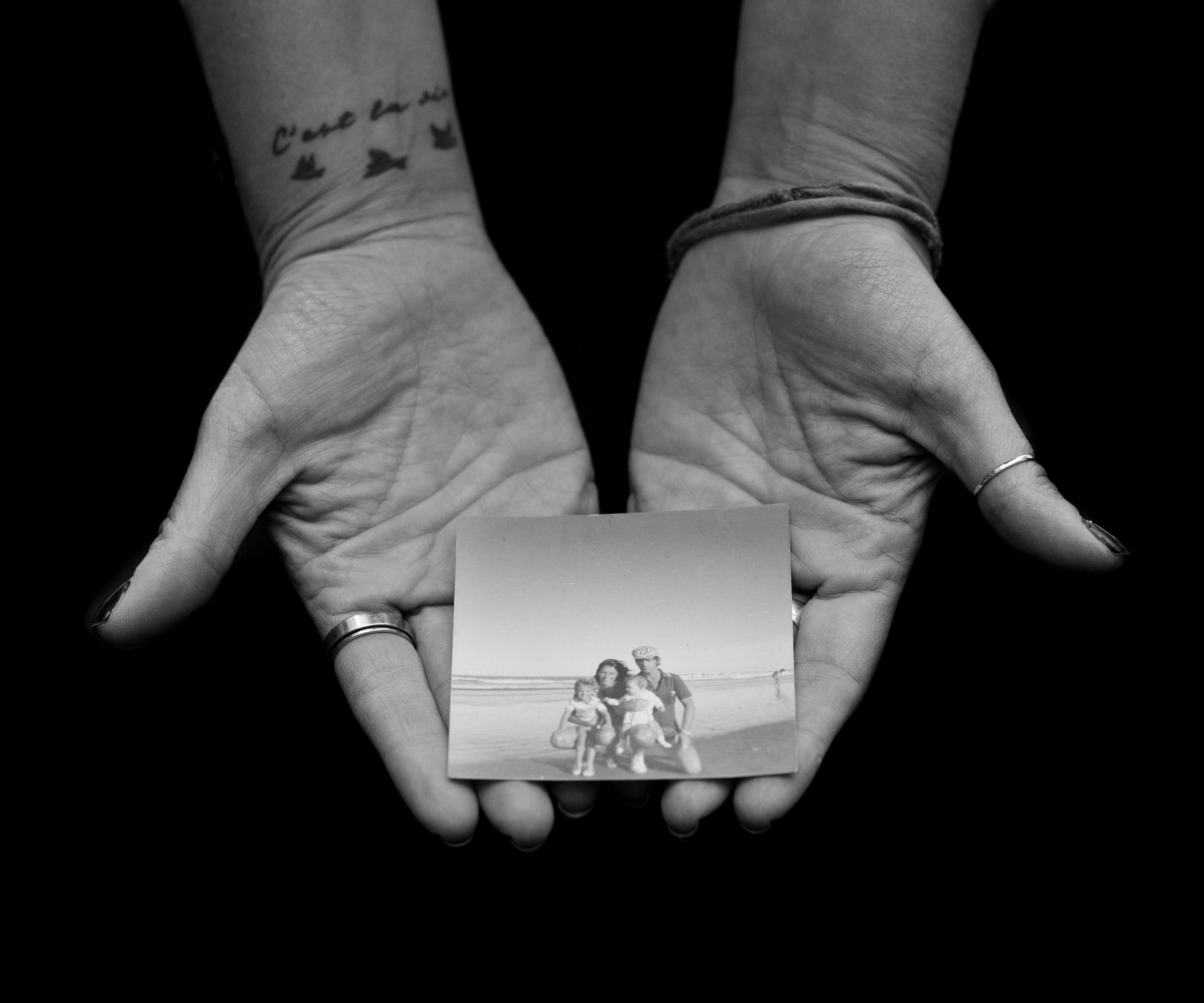

When Raquel Camps was an infant and her brother Mariano was three, they and their mother, Rosa María Pargas, were abducted by military forces; and their father, Alberto Miguel Camps, who had survived the Trelew Massacre, was killed. Three weeks after their abduction, the siblings were returned to their grandmother, but their mother was never seen again. To this day, Raquel has one, and only one, photograph of herself with her dad, her mom and her brother. She calls the image mi tesoro—my treasure.

Raquel Camps has a robe—a beautiful robe—that belonged to her mother, Rosa María Pargas, who was abducted by the Argentine military and never heard from again. The robe was given to Rosa by other inmates of the detention center where she was held as a political prisoner. The robe is also emblematic of the estimated 30,000 Argentine desaparecidos—citizens who, as a matter of official government policy, were disappeared.

Two years before Eduardo Adolfo Cappello was born, his uncle, also named Eduardo Adolfo Cappello, was killed in the Trelew Massacre. Two years after young Eduardo’s birth, his father, mother and brother were disappeared—abducted by a military gang that invaded their home. Eduardo was raised by his grandparents and grew up amid feelings of fear and terror and a painful need to hide his own identity, which could connect him to relatives who had been targeted by the military regime. Despite the fear, pain, and loss, his grandparents raised him surrounded with love and guided by a sense of purpose in seeking justice. For all of that, and in honor of his brave grandmother Soledad, who worked for justice until she passed away in 2016, he volunteered to be a named plaintiff in a lawsuit against Roberto Bravo, one of the soldiers responsible for the Massacre.

Carlos Juan Cappelletti’s uncle was Carlos Alberto del Rey, who took up the struggle against the dictatorship as a student of chemical engineering in the city of Rosario. Del Rey was shot to death in the Trelew Massacre at the age of 23.

One way of preserving the memory of an event like the Trelew Massacre is through the dedication of public spaces. María Angélica Sabelli, a fusilada, graduated as a high school student from the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires. In August 2022, a large room at the Colegio was dedicated to her memory, where a slide show about her life was shown and a plaque in her honor unveiled.

On the 50th anniversary of the Trelew Massacre, two of the three daughters of Ana María Villarreal, Ana and Gabriela (pictured here with Gabriela’s daughter, Maria de los Ángeles) stood before a plaque dedicated to their mother in the place where she was killed—the Almirante Zar Naval Base. Ana María Villarreal was one of five women who were shot that day, four fatally. Women played an important role in the resistance to the dictatorship and often paid an especially harsh price for their activism, including assaults and rape in prison and an estimated 500 newborns taken from their “disappeared” mothers and given away to police and military families.

Clarisa Lea Place is a young visual artist in Buenos Aires. She bears a strong resemblance to her aunt of the same name, who was among those killed in the Trelew Massacre. Clarisa, the aunt, was a law student and political prisoner, first arrested after distributing food to the poor. Along one wall of her niece’s small apartment is a series of hand drawings of a menacing soldier, advancing toward the viewer—the first makings of what looks to be a startling animated film about violence and resistance.

For years, relatives of those who were killed in Trelew have pressed the Argentine authorities for remembrance and justice—in time, with some success. Among others, Luisa Kohon, sister of fusilado Alfredo Kohon, was in the courtroom in Rawson in 2012 when soldiers Emilio Del Real, Luis Sosa and Carlos Marandino were sentenced to life imprisonment for malicious homicide in the Massacre, which the judge declared a crime against humanity. “I never imagined that everything that happened in 2012 would happen,” Luisa said at the time.

After having spent two horrific years in prison for her resistance to the dictatorship in Argentina, Silvia Hodgers, a professional dancer, has been living an “exile of atonement” in Switzerland. She is the subject of a 2001 film entitled Juntos, un retour en Argentine [Together, a return to Argentina], in which, having gone back to Buenos Aires, her past and present combined to tear her apart and to nourish her art and life. As she says in the film, “I’ve changed in the past 20 years; I am another woman even though I’m the same, but there are very deep marks that are impossible to erase.”

Mariano Pujadas was one of those killed in the Trelew Massacre, a week after giving a press conference and turning himself in at the old Trelew airport. His death was not, however the end of tragedy for the Pujadas family, who had originally come to Argentina to escape the fascist repression of Francoist Spain. On August 14, 1975, a paramilitary group stormed the Pujadas family’s home and abducted, tortured and killed those who were at the house: Mariano’s parents, his brother José María, and his sister María José. José María’s wife survived but died months later from her injuries. The two children at the house, Victor, 11, and María Eugenia, an infant, were left behind. Mariano’s nephew, also named Mariano Pujadas, is completing a film about these terrible events. Here, Mariano shows an iconic photograph of his uncle speaking to the press at the Trelew airport a week before his death.

Woven throughout the commemoration of the Trelew Massacre was the public recitation of the names of the fusilados, the 16 who were struck down in a hail of military-issue bullets and the three who survived with grave wounds only to be killed by the military in later years. After each name was called, those in attendance raised a hand and cried, ¡Presente, Ahora y Siempre! [Present, Now and Forever!]—a powerful and unifying ritual of memory and solidarity.

At a communal meal in Trelew, one such Recitation of the Names was led by Ilda Bonardi de Toschi, the widow of Humberto Toschi, who was murdered at the Trelew Massacre:

The Dead

Carlos Astudillo Miguel Ángel Polti

Rubén Pedro Bonet Mariano Pujadas

Eduardo Cappello Carlos del Rey

Mario Delfino María Ángelica Sabelli

Alfredo Kohon Humberto Suárez

Clarisa Lea Place Humberto Toschi

Susana Lesgart Jorge Ulla

José Mena Anna María Villareal

The Wounded

María Antonia Berger

Alberto Miguel Camps

Ricardo René Haidar

The 50th anniversary commemoration of the Trelew Massacre gave rise to many forms of artistic expression as means of remembering. One of these was an astonishingly beautiful work of dance theater in memory of Jorge Ulla, a victim of the Trelew Massacre, and in honor of his brother, Julio, who loved him immensely. The work, created in part by Julio’s daughters Marcelina and Juliana and performed by the Pana dance company, was entitled Jorge una generación que eligió por qué vivir, por qué luchar y por qué morir [Jorge, a generation that chose why to live, why to struggle, and why to die]. As Jorge once wrote to his father, “I am part of a youth that must fight against injustice.”

One of the culminating events of the 50th anniversary commemoration of the Trelew Massacre was a mass rally in front of the Centro Cultural por la Memoria [Cultural Center for Memory], where an elevated stage had been erected for the families of the victims of the Trelew Massacre. At the end of the rally, representatives of the Argentine Ministry of Defense presented each family with a dossier of once secret, now declassified military files pertaining to their relative. Among those on stage were Julio Ulla, brother of fusilado Jorge Ulla, and his daughters Marcelina and Juliana.

The 50th anniversary of the Trelew Massacre was observed not only by the victims’ generation and their children, but also by the children’s children. Among the many modes of expression that came out of the commemoration was a video, edited by the Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales [Center for Legal and Social Studies] or CELs, an Argentinian human rights group, of some of the grandchildren being interviewed. In the words of one grandchild, “History is obviously important in order to know why we are here and how we got here.” Or, to quote the original song Trelew by Lautaro Cerruti Camps, Alberto’s grandson, from the video’s soundtrack,

Trelew soy yo … Trelew sos vos … Trelew es memoria

Trelew is me … Trelew is you … Trelew is memory

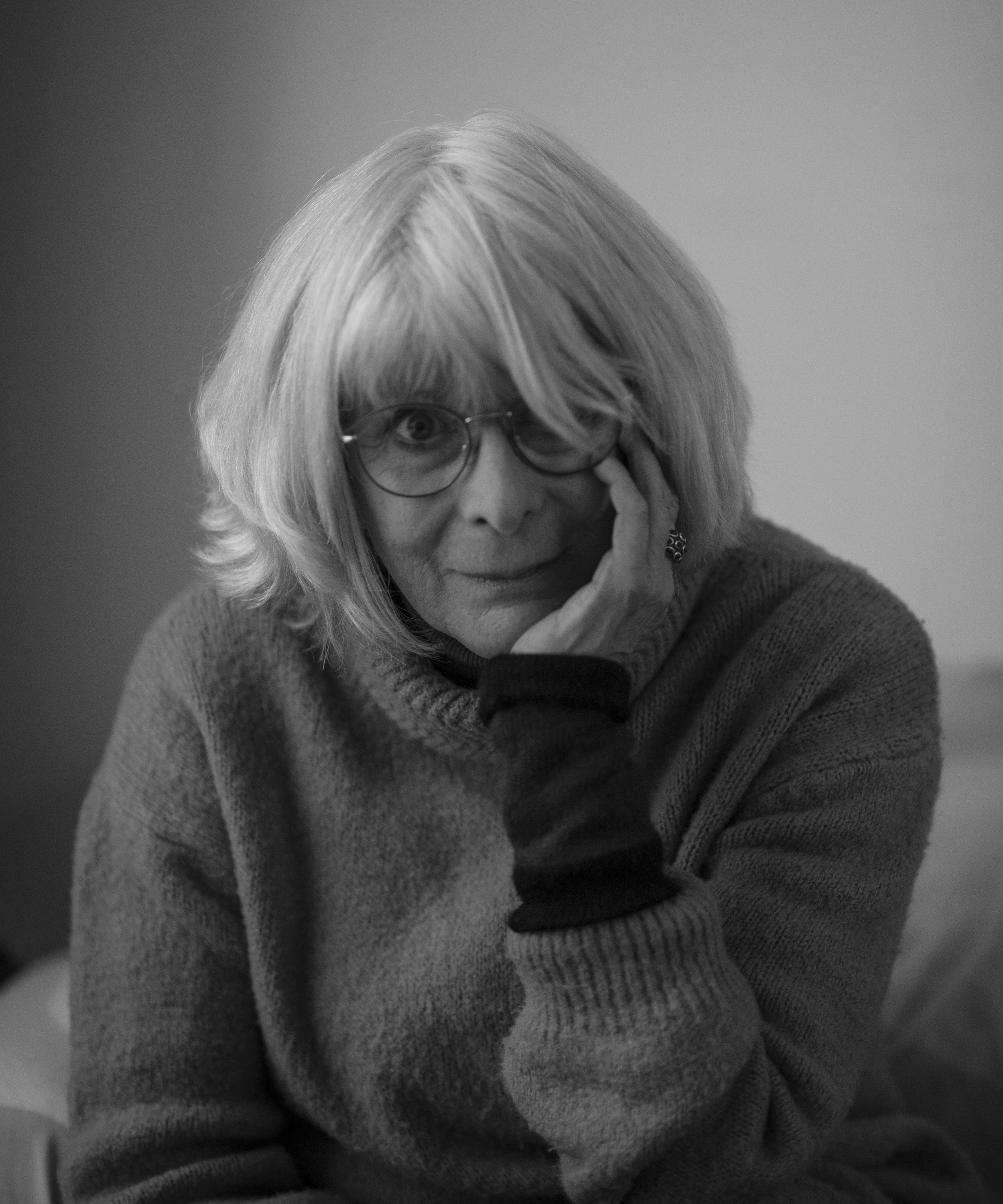

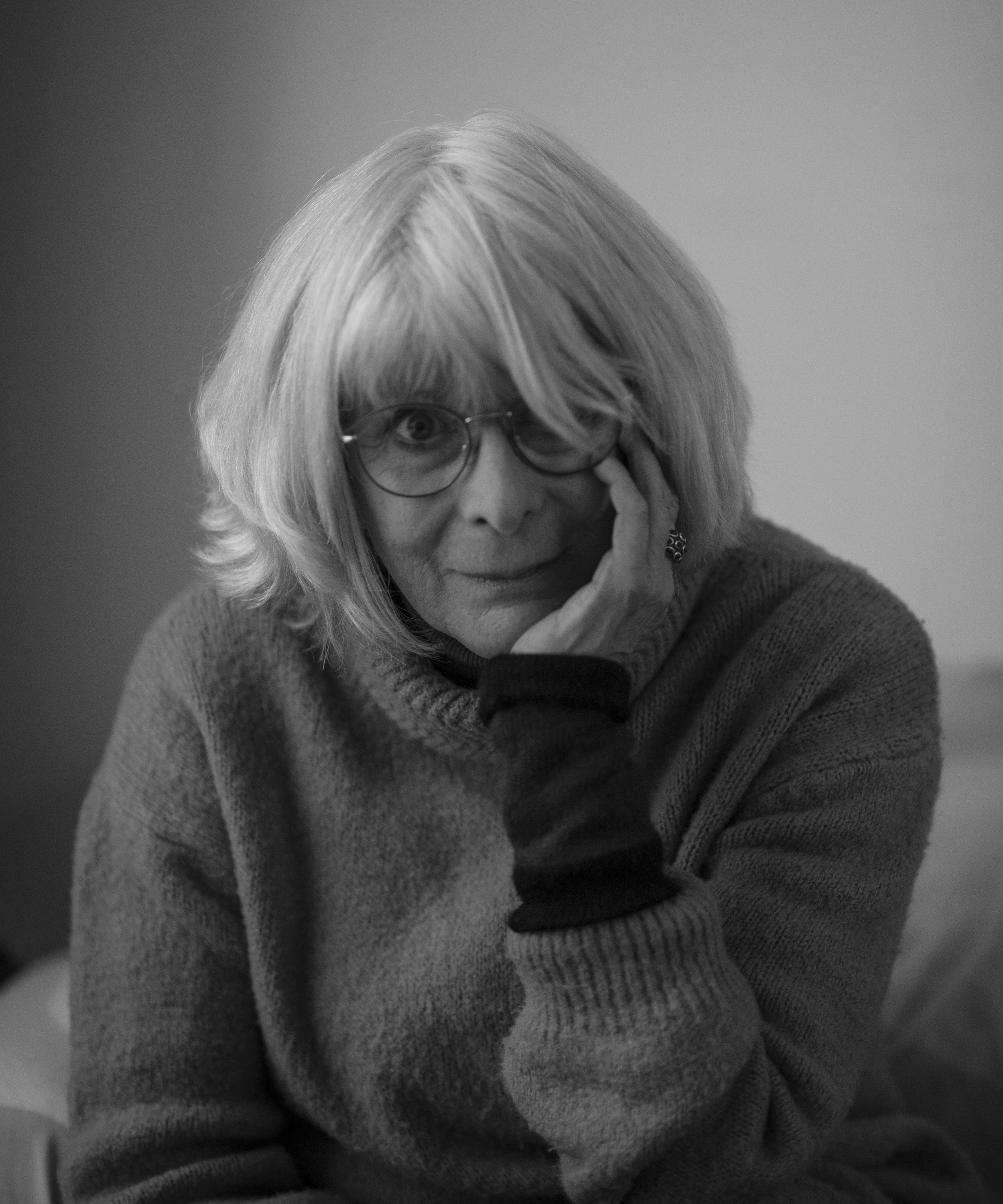

The human rights activist Taty Almeida spoke powerfully at events commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Trelew Massacre in both Buenos Aires and Trelew. The kidnapping and disappearance of her 20-year-old son Alejandro in 1975 by the right-wing paramilitary group Triple A led her to become an outspoken member of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and begin a tireless struggle to find her son, and to work for the values of memory, truth and justice. Her portrait is on permanent display in the Bicentennial Museum in Buenos Aires.

Encarnación Díaz was 44 years old in 1972, a teacher in Trelew and the parent of a political prisoner. She and other local residents visited inmates at the prison in nearby Rawson, brought them care packages, and helped break their isolation. For their activism, 16 of them were arrested and taken to Buenos Aires, more than 900 miles from their hometown. But the people of Trelew organized, occupied the town’s Spanish Theater and initiated a general strike until everyone was freed months later. An iconic photograph shows Diaz addressing a packed theater shortly after her release. Seen here speaking at the Almirante Zar Naval Base during the Trelew Massacre commemoration, Diaz remembered the actions as “an extraordinary model of popular organization.”

In 2020, with the help of the human rights group Center for Justice and Accountability, the families of four of the prisoners shot in the Trelew Massacre filed suit in Miami against Roberto Bravo, an officer involved in the shooting who moved to the United States in 1973 and never stood trial in Argentina. A key witness in the case was Dr. Rodolfo Guillermo (“Willie”) Pregliasco, a physicist and forensic expert who had undertaken a detailed reconstruction of the crime scene, including determining bullet trajectories. His testimony showed Bravo’s claim that the soldiers fired in self-defense as the prisoners charged them to be wholly inconsistent with the physical evidence.

Ilda Bonardi de Toschi is the widow of Humberto Toschi, one of those who was killed in the Trelew Massacre. She spent 50 years working to keep her husband’s memory and that of the Massacre alive, and to seek justice for the victims. Along with Sara Kohon, sister of fusilado Alfredo Kohon, and Silvia Pecci, human rights activist and member of Agrupación Todos los 22 de Agosto [the “Every 22nd of August Group”], she helped organize the 50th anniversary commemoration of the Massacre in Trelew, which included mobilizing and making arrangements for the more than 800 former prisoners, activists, family members of the victims, and officials who were present. Her work in this regard has contributed decisively to keeping alive the memory of the Massacre in all its historical significance.

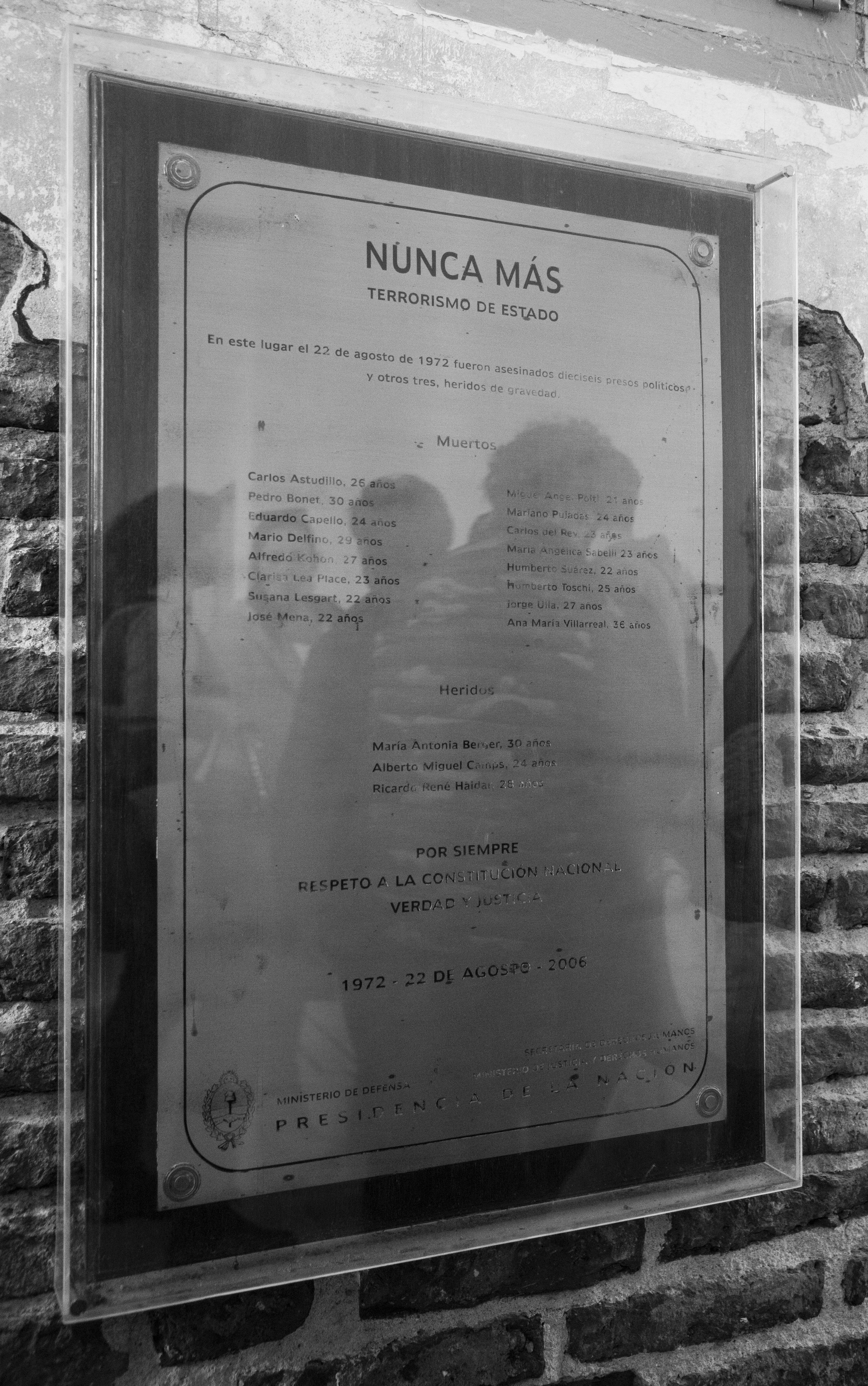

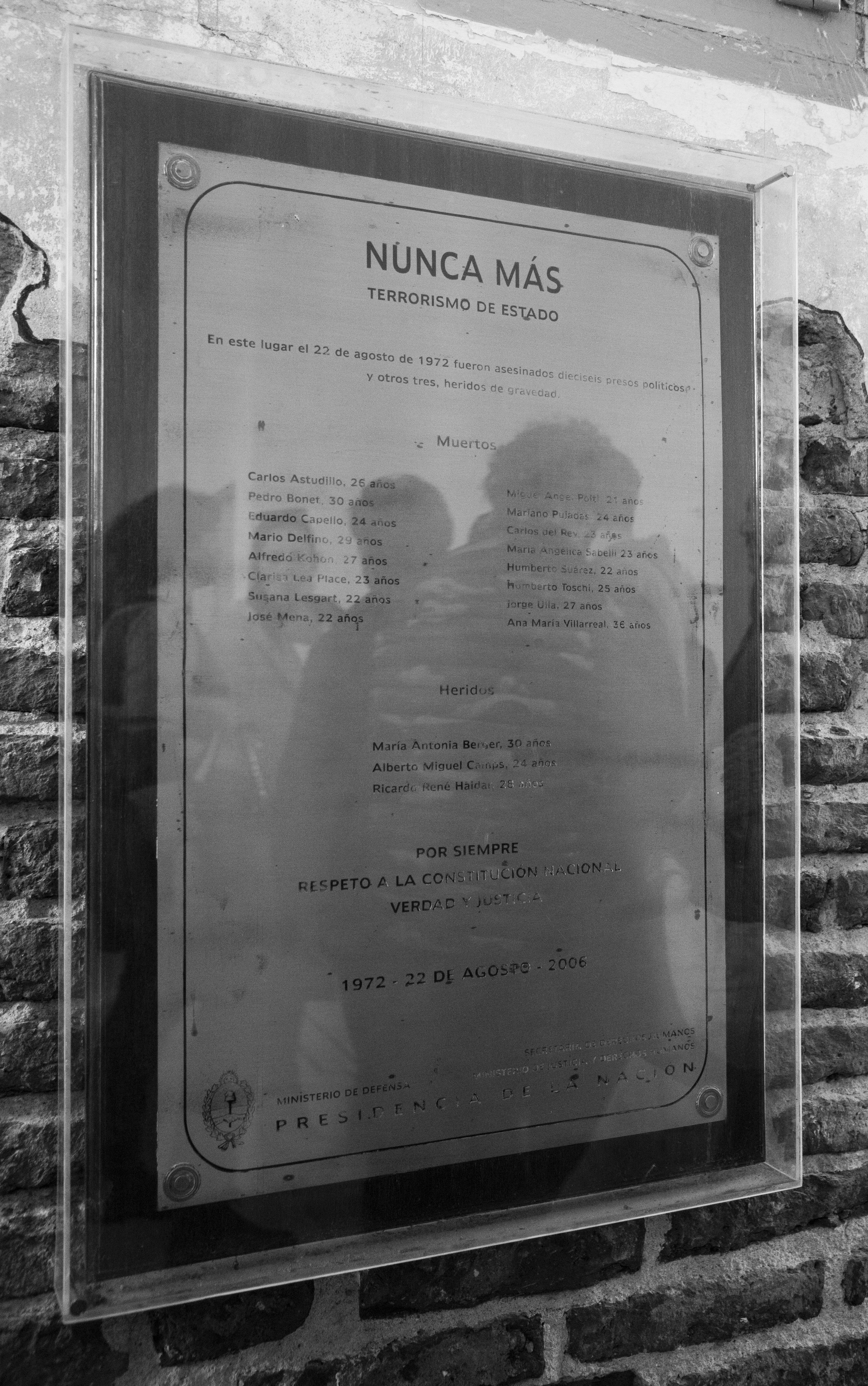

Echoing a sentiment that arose in the wake of the Holocaust, the phrase Nunca Más—“Never Again”—has also been applied to the repression and brutality of Argentina’s dictatorship. Bearing the same maxim, this plaque appears in the place where the Trelew Massacre happened and is subtitled, with remarkable frankness, Terrorismo de Estado [State Terrorism]. It goes on to list the 19 fusilados and then proclaims, Por Siempre, Respeto a la Constitución Nacional, Verdad y Justicia [Forever, Respect for the National Constitution, Truth and Justice].

Days before the 50th anniversary of the Trelew Massacre, this plaque was cemented into a sidewalk in Buenos Aires, reading,

19 Rosas Rojas Siguen Floreciendo

En Memoria, Verdad y Justicia

50 Años de Lucha, Unidad y Solidaridad

Familiares y Ex Presas y Presos Políticos

Barrios x Memoria y Justicia

[19 Red Roses Keep Blooming

In Memory, Truth and Justice

50 Years of Struggle, Unity and Solidarity

Relatives and Ex-Political Prisoners

Neighborhoods for Memory and Justice]